Introduction

I started using RCS in the 1990s because version control is a dang good idea. I have had a lot of professional experience with CVS and Subversion. Eventually (in about 2008) I personally settled on Mercurial. However, the rest of the world seems to have just figured out that version control is good and, thanks to GitHub, they have all gravitated towards Git. Like this guy I do have some minor problems with Git/GitHub, etc., etc., but overall it’s fine. If you think you should use it, then you definitely should. Here are some notes to myself about Git for when I’m working with others who require it.

John Carmack tweets…

I need to work on my knee-jerk hostility to learning about source control systems and build systems, but I just prefer working on actual programming…

— John Carmack

And.

Anyone that has me on too high of a pedestal should see me fumbling around with git.

— John Carmack

Resources

-

Lots of collaborative binary assets? My blog post on why Git may not be right for you.

-

Those dreadful Windows line endings can be dealt with.

-

Official Simple Tutorial

-

Github Services Cheat Sheet.

-

Radicle - Tries to replace Big Git Brother with a peer-to-peer rave party. Blockchain! Blockchain! Drop the base!

The Normal Thing

Here are the two commands I use 95% of the time.

git clone https://github.com/ros/ros_comm

git commit -aI’m pretty sure the -a is to allow you to skip git add for all

files. You could add specific files individually to a commit with

git add.

Here’s what I’m doing a lot of recently because I am often rebuilding a group project. This also hints at how to do all the other stuff.

ssh -i ~/.ssh/gh_rsa -T git@github.com # Load my key.

GIT_SSH_COMMAND="ssh -i /home/xed/.ssh/gh_rsa" git clone https://github.com/cxed/my_lil_projectThis is typical. The project has been cloned locally and it is being worked on daily. Edit something and make the changes available to others.

vim ~/myproject/README.md

git commit -a

GIT_SSH_COMMAND="ssh -i /home/xed/.ssh/gh_rsa" git push origin masterWhat if it still really insists that you use passwords? This can happen when you clone the project using https but then want to fix something and push a commit with SSH.

I had some annoying struggles with it wanting to default to passwords,

but I think this is a pretty explicit syntax that probably will be

more robust for normal GitHub work. Note redefining SSH to include the

special key set you want to use. Also note the protocol of the URL and

the weird use of the git login name therein.

export GIT_SSH_COMMAND="ssh -i /home/xed/.ssh/special_rsa"

export REPO="customer/customer_special_project"

export GH_URL="ssh://git@github.com/${REPO}"

git clone $GH_URLAnother normal task is to get your old local copy updated with what

your collaborators have checked in. Remember that there is no "update"

command in Git. See this section for details on using

pull instead.

git pull $GH_URL

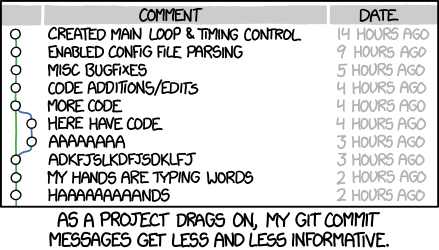

git push $GH_URLCommit Message Style

XKCD shows us what not to do.

I kind of like this convention system for commit messages. Start commit message with one of these.

-

feat: a new feature

-

fix: a bug fix

-

docs: changes to documentation

-

style: formatting, missing semi colons, etc; no code change

-

refactor: refactoring production code

-

test: adding tests, refactoring test; no production code change

-

chore: updating build tasks, package manager configs, etc; no production code change

It is also recommended to style the commit messages with something like this.

Add bozo detectionAvoid stuff like this.

Add bozo detection.

Added bozo detection

We're detecting bozos nowI think of it as answering the question, if this commit is applied, what will transpire? This first line is really the "subject" line of the commit message which is often all that is needed.

fix: Remove periods from commit message subject

This is a body and many commits don't really need one. Keep it under

72 characters. Keep the subject under 50! Do keep a blank line between

the subject (first line) and the body if one is included. The summary

line is what is used by the `git log` commands.

More paragraphs are ok; separate with a blank. The final section, also

optional, is the footer which can contain references to other things.

A sample footer follows this paragraph.

See also: #123, that_other_thingAndrey’s style is interesting too. He starts messages with a symbol.

-

+ some new thing or feature (code added)

-

= minor change (mostly equal to previous stuff)

-

* fix the bug (think of the asterisk as a squished bug)

-

- deprecated feature (code subtracted)

That may be a more compact approach.

Some Other Fun Things

Note that commit IDs can be shortened to the shortest unambiguous first characters.

git commit -a -m "Just like CVS."

git log

git log --stat

git diff 73af53a43bb09dcc6600478898c18cae53e57cf5 292faae8b1d912f93f3194f107acaabc6194ef96

git diff 73af 292f # Or shorten these hashes as you like/can.

git checkout b067 # Get the commit specified.

git status # Shows changed files.

git show 292faae8

git diff # Shows changes between working dir and staging area.

git diff --staged # Chages between staging and most recent commit.

git reset --hard # Ditches any changes in pwd or staging area. Caution!

git checkout master # Seems to get the latest commit.Ever wonder how many lines of code are in your project? Or bytes? Github does a crap job of sharing that with you (presumably because worrying about code bloat is not something tech bro hipsters in Silicon Valley ever do). But if you have the repo locally, this can work.

$ git ls-files | xargs wc -l

2 README.md

120 ashellscript.sh

207 monitor_thething.py

482 importantbit.py

181 datawrangler.py

196 actuator.py

129 masterplan.py

1317 totalDid you just obtain a giant sprawling repo and you need to make sense of it? My first thought was: what are the other contributors working on right now? I don’t know if I’m doing something wrong but when I clone a repo, I get all of the files unhelpfully timestamped right at the moment of cloning. Wouldn’t it make a lot more sense to have them time stamped as when they were committed? Oh well. How do you even see those commit times? This command can give you a list of all the files currently in your repo in chronological order.

git ls-tree -r --name-only HEAD | \

while read F; do

echo "$(git log -1 --format="%ad" --date=iso-strict -- $F) $F"

done | sortIf you want to temporarily mess up your tracked code git stash can

save temporary snapshots in what looks like a stack — there are git

stash push (the push is optional there for that effect), git stash

pop, and git stash drop commands. You can see what has been stashed

with git stash show. Details about it can be found with git stash

--help.

Configurations

git config --global --editAfter doing this, you may fix the identity used for this commit with:

git commit --amend --reset-authorAnother thing you can do is create a file called

${MYREPO}/.git/info/attributes which contains something like this.

*.png binary

*.jpg binary

*.jpeg binary

*.zip binary

*.gz binaryIn theory this should keep Git from going crazy diffing binaries. I’m not sure this is necessary. There may be global mechanisms in place that understand such things.

Here’s one that probably will be taken care of in sensible

environments with good .bashrc files. But if the EDITOR environment

variable is not set, consider this.

git config --global core.editor "vim"Sometimes if you are unlucky you get some guff like this when you’re trying to push some changes.

$ GIT_SSH_COMMAND="ssh -p222" git push

...

remote: error: refusing to update checked out branch: refs/heads/masterThis happened when just trying to coordinate two versions being worked on by two people (no GitHub nonsense) on two computers.

I fixed that with this cryptic nonsense.

git config --bool core.bare trueCreate A New Repository

With some extant files.

cd my_lil_project

git init

git add file1

git commitBranching

Show the currently checked out branch.

git branchShow the whole branch graph topology using something like this.

git log --graph --oneline mybranch master

git log --graph --allStart a new branch.

git branch mynewbranch

git checkout mynewbranch # Will output "Switched to branch 'mynewbranch'"Or this is a shortened equivalent syntax.

git checkout -b mynewbranchMerge

Ok, you’ve branched. How do you bring things back together.

git merge master mynewbranchDelete branch. This only deletes the branch name. The commits are preserved.

git branch -d mynewbranchMerges with conflicts can be spotted when the git merge command

produces a message like this.

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in myfile.cppThis can leave a bunch of redundant stuff which needs to be cleaned up.

<<<<<<< HEAD

pi= 3.14159265359 # My change.

||||||| merged common ancestors

pi= 3.141 # The code that was here originally.

=======

pi= 3.141592 # Someone else's change.

>>>>>>>Make sure when resolving conflicts to remove any of the redundant code

and any of the section delimiters. Use git status to monitor

conflict issues. Fix the issue by removing all the diff clutter and

settling on correct content. Then do git add to put this new version

into the staging area. Then git commit; you shouldn’t have to enter

a commit message since it will automatically default to remind you

that this commit was basically about resolving the merge problems.

Fast-Forward Merges

Many operations use merges behind the scenes. If the A is a direct ancestor of B, then merging B and A is a "fast-forward merge" where the label simply can be moved since B knows all about A because the topology simply points back to it.

Merge With Another Project

Let’s say you’ve started a project and then you realize someone has a project that is similar to yours with a lot of stuff you like and you want their project to be incorporated into yours.

cd MyBigProject

git remote add BigProjectTemplate https://github.com/otherguy/BigProjectTemplate

git fetch BigProjectTemplate

git merge --allow-unrelated-histories BigProjectTemplate/master

vim fixconflicts

git add newfile # Maybe created to avoid a conflict, maybe a second `README.md`.

git commit -a

GIT_SSH_COMMAND="ssh -i /home/xed/.ssh/gh_rsa" git push origin masterLater maybe the BigProjectTemplate folks have fixed some important

things that you’ve pulled in. You might get a message like this.

This branch is 9 commits ahead, 15 commits behind BigProjectTemplate:master.You need to do git push to get your 9 commits up to GitHub.

Checkout your local master branch, do git pull. This will pull the

15 commits that you’re behind. Switch back to your development

branch, and do git merge master. Then you’ll want to do another git

push to get the merged version into your GitHub branch.

This is also the same situation when you have a collaborator who doesn’t register with your project as an official collaborator but rather keeps their own repository. Here’s an example of coordinating a merge, basically the same as shown before.

git clone https://github.com/cxed/coolproject.git master

git pull https://github.com/ThatGuy/coolproject.git master

# Fix any merge problems if any.

GIT_SSH_COMMAND="ssh -i /home/xed/.ssh/gh_rsa" git push origin masterRename Files

It’s mostly as simple as taking your up-to-date repository and doing something like this.

git mv badfilename goodfilename

git commit

git pushRenaming a Github repository is more involved and requires admin privileges. Check the "settings" tab of the project.

What if your project is becoming more complicated and you want to push some things into subdirectories? Renaming also works for that just fine. Here I’m tracking a Python module where I started collecting so many examples using it that I wanted to separate them from the main module code.

$ mkdir examples

$ git mv location.py examples/

$ git mv timestamps.py examples/

$ git mv weather.py examples/

$ git add examples

$ git status

On branch master

Your branch is up to date with 'origin/master'.

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

renamed: location.py -> examples/location.py

renamed: timestamps.py -> examples/timestamps.py

renamed: weather.py -> examples/weather.py

$ git commit -a

$ git pushNote that git mv actually does the moving in your file system too.

GitHub

-

The proper URL: https://github.com/

-

To log in directly: https://github.com/login

Where Did This Code Come From?

Ever find yourself with a Github repository and actually had no idea where it came from? Obviously Git knows and here’s one way to make it tell you.

$ grep url .git/configGitHub has a nasty habit of pumping personal email addresses into the wild web. There is a "privacy" email that you can use. While logged in go to /settings/emails and Keep my email address private and Block command line pushes that expose my email. Then for good measure you can configure your command line local user account’s git settings like this.

git config --global user.email "cxed@users.noreply.github.com"And check it like this.

$ git config --global user.email

cxed@users.noreply.github.comActually it can be a bit more involved now! If you get a message

saying, push declined due to email privacy restrictions you can fix

it following the advice described

here.

First find your magic Github "privacy" email address. This can be

found here: https://github.com/settings/emails Then change

to it in your CLI configuration. Mine looks something like this (but

this is not exactly it!).

git config --global user.email "49999999+cxed@users.noreply.github.com"

git commit --amend --reset-authorIf you do that and try your push again it should now work out. Still, you pretty much should assume a complete breakdown of email privacy.

SSH

Go to your identity icon and then "Settings". Then choose "SSH and GPG keys". Then "New SSH key". When you paste the public key don’t worry about all the messy hard returns. It sensibly strips that all out. GitHub will then show you the md5 fingerprint if the key was successfully accepted. You can check locally if it matches with this.

$ ssh-keygen -l -E md5 -f /home/xed/.ssh/github_rsa

2048 MD5:b7:63:d6:03:8c:91:63:04:dd:e3:be:5a:c5:61:1e:1f xed@usb64 (RSA)(Looks like you don’t need to have the -E md5 option now. The

default hash output seems to match better with what Github shows.)

Once GitHub has your SSH key you can

test

it. Note that the user to use is git, not your real GitHub

username.

:->[usb64][~/.ssh]$ ssh -T git@github.com

Host key fingerprint is SHA256:nThbg6kXUpJWGl7E1IGOCspxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

+---[RSA 2048]----+

| =+o...+=o.. |

|o++... *o . |

|*.o. *o. |

|o.. ..o.= . |

|o.. ..o.= . |

|o.. ..o.= . |

|OE . . o |

| o . |

| |

+----[SHA256]-----+

Hi chrisxed! You've successfully authenticated, but GitHub does not provide shell access.If everything goes very well, this may even load your SSH key’s password into an agent so you won’t have to worry about authentication again during this session.

The Problem Of Multiple Keys

I had problems because I had two keys that went to two separate GitHub accounts. This is how one can clarify which key to use.

$ ssh -i ~/.ssh/gh_rsa -T git@github.com

$ GIT_SSH_COMMAND="ssh -i /home/xed/.ssh/gh_rsa" git push origin masterWell, that’s super annoying.

Git Refuses To Use SSH

What if you set up SSH and it still refuses to work? If it insists on

an HTTPS password it might be because you cloned the repo using HTTPS

but then want to work with it with SSH. The cure I found was to look

in .git/config. Here’s a tiny excerpt from a configuration that

does work with SSH.

[remote "origin"]

url = ssh://git@github.com/cxed/ateamBasically replace https:// with ssh://git@.

Creating A New Repository

It seems like to create a repository on GitHub, you have to use the web interface and do it from the web site. All subsequent operations can be done using the command line. While logged in look for the "+" sign in the top right menu. Click that and choose "New repository". Here I’m calling it "probe" (i.e. just a test); interestingly I do not have to call the working directory the same name.

$ git remote add origin https://github.com/chrisxed/probe.git

$ git remote

origin

$ git remote -v

origin https://github.com/chrisxed/probe.git (fetch)

origin https://github.com/chrisxed/probe.git (push)

$ git push origin master

Username for 'https://github.com': chrisxed

Password for 'https://chrisxed@github.com':That’s how you do it for using the web authentication credentials… But I wanted to use SSH keys. Make sure you select SSH and not HTTPS from the GitHub website after you make your repository there. Git rid of the incorrect "remote" named "origin".

$ git remote remove origin

$ git remote add origin git@github.com:chrisxed/probe.git

$ git remote -v

origin git@github.com:chrisxed/probe.git (fetch)

origin git@github.com:chrisxed/probe.git (push)

$ git push origin master

Host key fingerprint is SHA256:nThbg6kXUpJWGl7E1IGOCsxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

+---[RSA 2048]----+

| =+o...+=o.. |

|o++... *o . |

|*.o. *o. |

|oo. ..o.= . |

|.+o. .. S = |

|.+o. .. S = |

|.+o. .. S = |

| o . |

| |

+----[SHA256]-----+

Counting objects: 6, done.

Delta compression using up to 8 threads.

Compressing objects: 100% (5/5), done.

Writing objects: 100% (6/6), 1.13 KiB | 0 bytes/s, done.

Total 6 (delta 1), reused 0 (delta 0)

remote: Resolving deltas: 100% (1/1), done.

To github.com:chrisxed/probe.git

* [new branch] master -> masterSince the key is decrypted and loaded in the agent, it runs immediately with no more fuss.

Files From Elsewhere

You can create new files directly in the GitHub website. Or maybe someone else (or you from a different computer) committed some new stuff. Here’s how to update what’s in your local copy.

git pullAnd if you want more control this is the explicit way to phrase the command.

git pull origin masterRemember that origin is the (arbitrary but conventional) name of the

remote and master is the branch to acquire. Basically push and

pull move things from remotes to branches and vice versa.

Forking

A fork is just a clone that GitHub makes for you on their own servers. GitHub also keeps track of the number of people who have made forks of your repository. If you don’t want to keep tentacles of the original project, just clone it locally. Then create a new project on GitHub, set a new remote for that new project and push it. Not having to do this is what forking is all about (but sometimes maybe that’s how you do want to play it).

Here’s some terminology topology where A,B,C,D are commits.

Local:

/----C

A<--B+

\----DLocal: Local:

- - - - - - - - - -

|A<--B<--C| |A<--B<--C|

- - - - - - - - - -GitHub: Local:

- - - - - - - - - -

|A<--B<--C| |A<--B<--C|

- - - - - - - - - -GitHub: GitHub:

- - - - - - - - - -

|A<--B<--C| |A<--B<--C|

- - - - - - - - - -Downgrading To Older Version

A subtopic of forking is how to use an old version or "downgrading". For example, if a project compiles against the latest CUDA libraries (ahem Meshroom) and Debian is taking its careful time about adopting those, you may want the older version of the project. To do this you’ll need the commit hash of the version you want.

Start by cloning the project’s ordinary repo, which will give you the latest.

git clone https://github.com/alicevision/meshroom/Then check out the specific version you need.

cd meshroom

git checkout f676b40Or here’s is a sensible variation on the theme described here:

git checkout devThat should be it. You can check that did what you wanted with git log.

Recovering A Deleted File

Let’s say you accidentally delete a perfectly good repo tracked file that was minding its own business. If you need to get it back do this. Note the circumflex.

$ git rev-list -n 1 HEAD -- whoops.txt

9689634848980ac73b724c759c5271a8dd30e6a1

$ git checkout 9689634848980ac73b724c759c5271a8dd30e6a1^ -- whoops.txtObtaining Only A Subdirectory

Often there’s a giant project and it will contain something like an

examples directory filled with different examples all in their own

directories. I don’t want all the examples I don’t want and I

definitely don’t want the entire project (which may be living

comfortably on my system as a distro binary). So how does one get a

subdirectory?

Well… It’s ugly. Very ugly. There are three ways I have heard of.

First is the absurd export to (from?) subversion. I’m not even kidding. Check out the details here. But what if you don’t have easy access to subversion?

The second method is probably the official Github method. This involves doing a sparse checkout. Here is a description of the process. I find that procedure kind of unnerving because it makes configuration changes which doesn’t seem quite right. Maybe you want a one time thing but normally you don’t want any surprising nonstandard behavior everywhere else you use Github. So I don’t know.

The third method is to give up. Don’t try to save bandwidth. If you’re not on a ship, you can take comfort in knowing that Microsoft will pick up the bill for moving those extra bytes.

git clone https://github.com/someone/cool_project

mv cool_project/examples/extracool cool_project-repo-extracool-example

rm -frv cool_projectIf someone knows the less awful way to do this, let me know!

Adding Collaborators

On the project’s repository page, go to "Settings" (right side menu). Then "Collaborators" (left side menu). Add the GitHub username of other contributors and click "Add collaborator".

If local changes have been made and it is likely that remote changes

from other collaborators have also been made, then safely update the

local copy with a branch to a new origin/master leaving the local

master alone.

git fetch # Updates the local copy of the remote branch (origin/master).So if you wanted to have access to all the changes that have been

applied remotely without incorporating them immediately into your

current commit use fetch. Note that these are equivalent.

git pull origin master # Is the same as the following...

git fetch origin ; git merge master origin/masterPull Requests

Basically I’m asking some project owner to pull in my changes. Or

something like that. Probably it would have been better named merge

request. There are a lot of tools on the web interface for requesting

this and approving it. I don’t know exactly what the story is on the

command line, but it’s probably not critical to me right now.

Operation |

Affects |

vim A |

local working directory |

git add A |

staging area |

git commit |

local master branch |

git pull origin master |

local master branch |

git push origin master |

GitHub master branch |

merge alt pull request |

GitHub master branch |

To send a new branch to GitHub as a new branch.

git checkout -b mynewbranch # Now on a new local branch.

git push origin mynewbranch # Make branch on GitHub.Often when you’re mucking around with some code cloned from someone else, it’s important to change the "base fork:" property. In the "Open a pull request" page, find that selector and change it to something less meddlesome to the official project (unless you really want to request that the official project pull your changes into it).

When a pull request has been made on your project, assuming no problematic conflicts, you will be able to do one of the following.

-

Create a merge commit (default)

-

Squash and merge

-

Rebase and merge

Once you’ve done the merge and seen the "Pull request successfully merged and closed" message, you can delete the branch by clicking the button that encourages you to do so.

Pull Request Conflicts

Sometimes you fork some project, clone it to your local system, make some changes, and push them back to your fork. But meanwhile, someone has made conflicting changes to the project you forked messing up your intentions of a pull request. You may need to clone not just your fork’s situation but also the new situation on the main project. Note I’m not calling it the "original" project because "origin" is a GitHub slang for the remote location used in push and pull. The name "upstream" is often given to the project you forked from. So to sort that out do something like this.

git branch mynewstuff

git checkout mynewstuff

... Make mynewstuff changes

git remote add upstream <source_project_URL>

git checkout master

git pull upstream master

git checkout mynewstuff

git merge master mynewstuff

... Manually resolve conflict if needed...

git add file_fixed

git commit

git push origin mynewstuffThis will push an updated version of mynewstuff to your fork which

will then stand a better chance of being accepted. Note you can’t send

it directly to upstream since that is probably not yours. You can

just send the "globally aware" version of your changes to your fork

and that fork’s status should get updated to say, no conflicts.

Delete Repo From GitHub

Sometimes you’re just testing (or some researchers at your university are caught in a vicious turf war which turns some of your little programs into hotly contested "intellectual property" which you are no longer allowed to benefit the world by making public) and you need to just completely get rid of a repo. This kind of URL will take you to the settings page.

At the bottom of that you’ll see a red section called "Danger Zone". There you will find a button to ditch the whole mess. "This action CANNOT be undone. This will permanently delete the $MYREPONAME repository, wiki, issues, and comments, and remove all collaborator associations." You must type in the name of the repository to confirm.

And one of my least favorite things about GitHub — a complete and valid reason not to use it — is that if you accidentally check in some sensitive information, it can be damn difficult to feel confident that you have cleaned up the mess. I know that BTC pirates were crawling GitHub for AWS API keys and AWS had to start preemptively doing that too. I’ve never had that problem, but I have accidentally checked in source code that contained a personal email that I really didn’t want to make public. I just nuked the repo as described above and recreated. But there may be slighty better ways. They sure look bleak though.

GitHub CLI

It tuns out that if you’re doing a bunch of fancy stuff with a bunch of other fancy people and you’re all merrily using Microsoft GitHub you will almost certainly be forced to use GitHub’s horrendous web interface, for example to generate pull requests. But there may be a way around that problem. There is an official GitHub project called GitHub CLI that is intended to be a way to avoid the horrid web mess.

Installing

To obtain it you’d think it would be only sane to build it from source. But I don’t really want Golang mucking up my hard drive, so a binary package it is! I don’t trust just putting a Microsoft repo in my apt sources. But this method seems fine.

BINPKG=https://github.com/cli/cli/releases/download/v2.8.0/gh_2.8.0_linux_amd64.tar.gz

cd /tmp ; wget -qO- $BINPKG | tar -xvzf - ; cp /tmp/gh_2.8.0_linux_amd64/bin/gh ~/bin/