Way back in June I mentioned that my health had still not quite returned to proper form. Although it was subtle and my overall health is very good, I could tell some things weren’t quite working as well as they had before I was sick. The circulation in my shins was probably the most noticeable. I also had occasional days where it felt like I was at high altitude. I felt sluggish and short of breath. Here is a good article that investigates many of the strange problems people are having long after their initial Covid19 experience would seem to be over.

I’m pretty active and never stopped being so. I was walking on our forest trails most days and biking more than 50% of the days, but I felt like I needed a more serious way to push my body. My feeling was that if there was a lingering pathogen, I wanted to burn it out. If there was slow repairing vascular damage or lung scarring, I wanted to push my body to tear it all out and do a complete overhaul. If I was going to drop dead from a blood clot or stroke, I wanted to do that sooner rather than later.

Thinking about how I might maximize physical activity (without doing some major bike touring), I thought back to my introduction to hardcore athletics and the brutal sport of indoor rowing. I’ve ridden the big climbs on the course of the Tour De France. I’ve ridden farther than cycling grand tours in shorter amounts of time. That’s hard, yes. But there’s something special about rowing which makes it even harder. Rowing uses your arms and shoulders and a pretty fair amount of upper body. And if you do it properly, you can pour an outrageous amount of power into rowing without getting damaged. Cycling is not bad for that but it is common to have knee problems or other issues when increasing cycling by an order of magnitude.

Although I’m told that modern cycling gadgetry is pretty fancy, the physics of it will never let it come close to indoor rowing for accuracy and precision of tracking performance. A proper indoor rowing machine is called an ergometer because of its accurate energy measurement ability. In the world of exercise equipment, there are all kinds of "rowing machines" one can buy. In the world of competitive indoor rowing, there is only one: Concept 2. I started rowing on a Concept 2 Model A which was a bicycle wheel with plastic paddles stuck to it on a chain.

Much of my high school training and learning the art of high watt suffering was done on a Model B.

In my 20s I bought a new model C, nearly identical to the model B.

I gave that up long ago and now I needed a new one, a Concept 2 Model D, still very similar to the B and C.

I was ready to buy one and… they’re very back ordered thanks to The Plague. Great. I signed up for the waiting list and did my waiting.

After a few months they finally sent me one. It is a very fine machine, designed to be constantly abused by some of the strongest people on earth — imagine training centers for Olympic rowers. I wasn’t going to break this thing, but I was going to give it my best shot.

What I wanted to do was to push my cardiovascular system to its maximum. Every day. For a decently long amount of time. I wanted it to be consistent so that I could spot anomalies easier. At first I started by doing a 5 minute piece at full gas. I’d do a 5 minute warm up and a 5 minute cool down. I did that for about two weeks before realizing that I often was strongest on the warm up. So I settled on three 5 minute pieces at full throttle. I figured this was like running a 5km race — not just a training jog — racing every day. The trick was to not do the 15 minutes continuously but to break it up to get much higher wattage closer to full gas racing. I think if you did a running 5km race every day, you would break yourself. But on a rowing machine, you just feel like you’re being waterboarded three times a day. Fun!

The process was to wait between pieces long enough to maximize wattage. But not so long that I cooled down. At first I thought this would allow the whole operation to be over in about 20 minutes but as my wattage grew, the recovery intervals went from a couple of minutes to between 5 and 10. I didn’t get too fussy about that, just whatever I felt would maximize wattage over 15 minutes of engagement.

As I started this program, I didn’t know how it would go. I didn’t know if it was sustainable (it totally is not). I didn’t know what to expect from myself. But after the first few weeks of making good improvements, I had a pretty ambitious goal to see if I could crack 250 watts for a 5 minute row. Many weeks went by where it seemed like I was on a trajectory to do that, but quite a long way into the future. However on my 85th day the stars aligned just right for me to pull off a blistering 254W! I started that record run feeling good but being surprised that I was only pulling 240W in the first minute. Then I realized I was hitting 340W! The first minute came in at 303W. I kept it together for minute two and knowing I was solidly on pace to break my goal, I was able to push well beyond normal performance for the gruesome painful minute 3 and 4. By the last minute, I knew I would succeed and the excitement of that knowledge elevated my performance even more. I was so happy that I then rowed an entirely respectable 242W on the next piece. (I’m not bragging because pretty much everyone who is serious about this sport is way better than I am, but if you’re playing along at home, you’ll want to be under 143.4lbs at some point in the day or under 145.2lbs right after your competitive attempt. If you’re tall and/or my brother, you’ll need to basically pump out 3.85W/kg for 5 min. Also you’ll need to be over 50 years old. Have fun breaking that one Al.)

But that stellar performance came at a cost. I was absolutely shattered for a couple of days after (as you can see below). It was about then that I set the project’s conclusion to 100 days — which was yesterday.

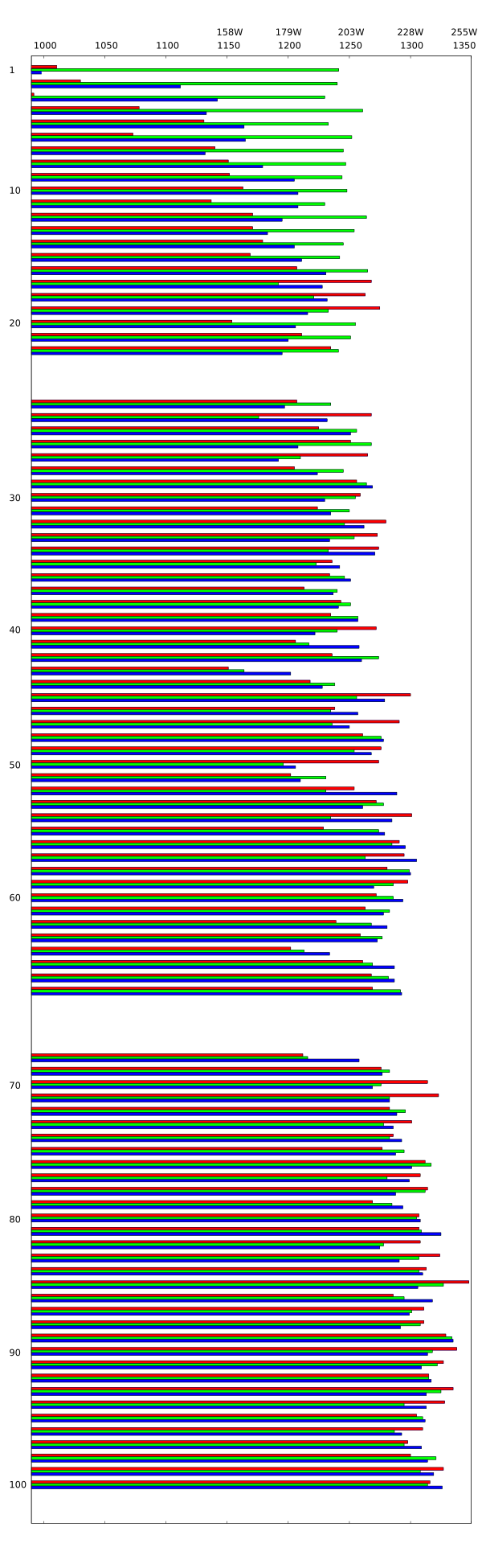

So how did it all go? Let’s take a look. Here is the "meters" recorded by the machine for all 300 five minute events. This corresponds very accurately and consistently with wattage (the machine’s physics allow it to calibrate itself every stroke). The days that are missing (at 22-23 and 67-68) are days I was away from my house and didn’t have access to the machine.

You can see that I started out imagining that I would push for strong performances after warming up, shown on the middle green bar. But after a couple of weeks I could tell that my performances cold were often better. This has always been true in my athletic career, but I thought being an old man would necessitate some changes. Nope. More often than not I can sit down cold (literally) and blast out my best possible wattage.

My astonishingly good performance on day 85 is clear to see. But that was not actually my highest wattage day. Can you spot it? Take a look at the next plot which shows the days' cumulative total meters.

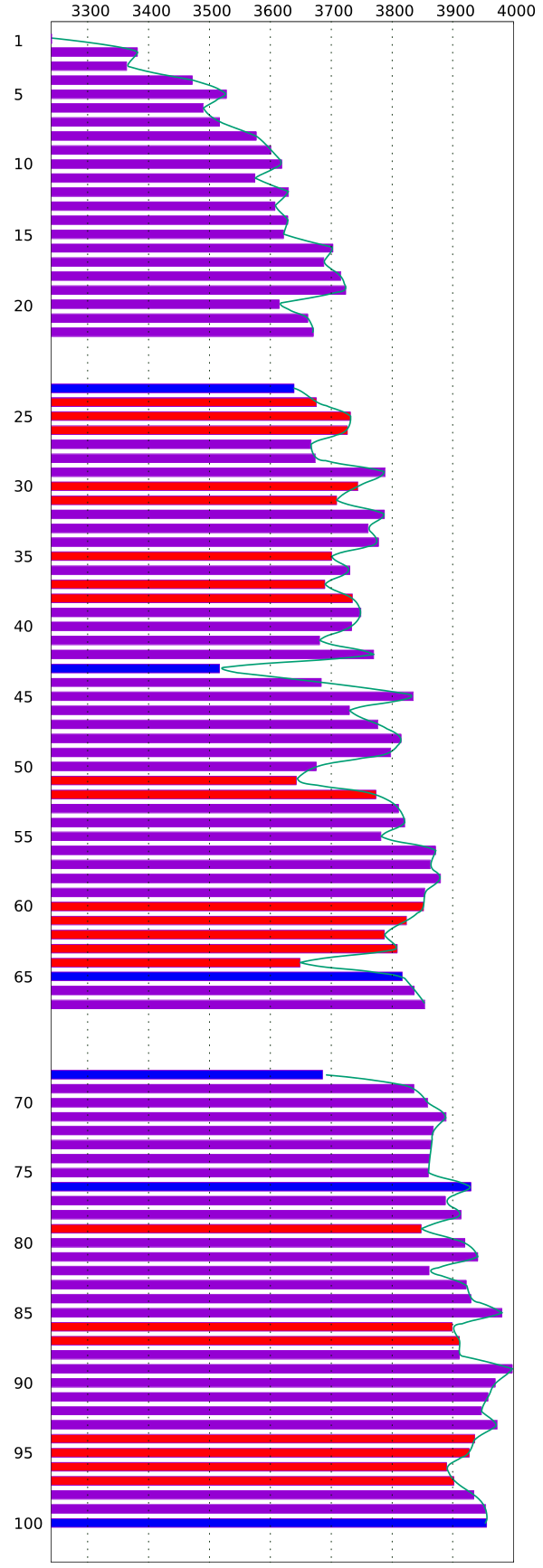

I let Gnuplot have fun with smooth mcsplines to make that green

line with the hope that it would sort of hint at the trends — and it

sort of does. The purple bars are unremarkable days — days where I

literally did not make any remarks in my training log beyond the

scores. The blue bars are days where I note some other kind of

significant activity. I still was walking the forest trails for about

20-30 minutes 5 out of 7 days or so. The blue bars are something

beyond that. For example, day 43, I biked 90 minutes. Biked 30 min on

day 76, a pretty good rowing day. Day 65 I skated for 30min (my feet

are still not completely healed from that). And if you were doubting

my dedication during the two out of town breaks, the rowing on days 23

and 68 were done after 7 hours of driving - fun!

Now we get to the interesting days, the point of the exercise. The red bars are days where my log noted feeling either ill, severely fatigued, suffering strange muscle pain, or strange breathing difficulty. For example, as I already pointed out, on days 86 and 87 I was completely toasted. Those days felt like I overdid it with the previous rowing. Makes sense. But other days, were more mysterious. The recent days, 94-97, were a challenge — those were what I call "high altitude" days where I feel like I’m at 3000m/10kft above sea level all day. I function fine at those altitudes, but it’s unnerving to feel this way at low elevation. To see that clear drop in wattage helped me feel like, ah ha, I caught this weird evil spirit in the act.

But overall I’m more reassured than worried. Clearly I’m not quite dead yet. I didn’t even drop dead while pouring out maximum wattage. I’m self-aware of my body enough to know that doing the equivalent of a 5km running race every day is probably not optimal for, well, anything. For example, atrial fibrillation in endurance athletes seems to be a real thing and I’d like to not know too much more about it. Apparently that affects cyclists, rowers, marathon runners, and, uh, cross-country skiers… Oh ya, that last blue bar was our first sufficient snow of the year and I was out skiing. Twice.

I definitely feel stronger and healthier than I did when I started this rowing project. That feeling now has some good data to demonstrate that while I may have suffered long term Covid19 damage in subtle ways, I’m not in too bad shape. Also my fitness can improve and has. Bad days now are better than good days two months ago.

My future plans with the rowing machine are a lot more sensible. I’ll probably keep doing some occasional 5 minute wattage tests, but not every day, and definitely not three punishing times daily. Hopefully I can shift to skiing more soon, but, you know, global warming… Next spring, I’d love to figure out a way to get back on the water in a real shell after decades of missing that beautiful sport.

UPDATE 2021-01-05

Ed Yong tipped me off to an interesting resource describing something called post-exertional malaise. Which apparently is a thing. While a lot of the descriptions of that ring true with me, I think my much higher than normal level of fitness masks the subtle effects. Was I fitter than normal people in 2019? Without a doubt. Would I be fitter than normal people if I lost 10% of that advantage? Of course. But I would notice the loss.

And that’s what my intense rowing agenda was trying to investigate. I enjoyed reading this from that web site:

"Questions have however been raised about the clinical use of the 2-day CPET procedure. Snell et al. suggested it might be unethical to use this method since many ME/CFS patients might suffer a serious relapse as a result of exercise performance."

(In other words, is it ethical to test people who might develop extraordinary malaise/fatigue problems because of the nature of exercise on their physiology, by having them exercise?) It was funny because I suspected the same thing and wanted to do to myself what would have been questionable to inflict on others: push my limits to see what the effects were.

UPDATE 2021-03-08

I spent much of February actually near 3000m in Colorado where I averaged around an hour or so of high-altitude Nordic skiing every day. Despite a long drive back to New York, the next day I was keen to see how my fitness would look on the erg. I was quite pleased to pull off 250W exactly (1341m, with a record first minute of 333W and a record stroke rate of 30spm). I felt strong while skiing in Colorado despite the altitude (ironically some breathing struggles at night trying to sleep). And now I feel quite fit even compared to my pre-plague level. I may sometimes still have strange days of weakness and fatigue, but I feel they’re becoming rarer and having less of an impact.

UPDATE 2021-03-27

Here is an excellent article about NBA players who have had Covid19 and how their recovery looks. It seems with athletes — and me — that despite seeming to have recovered, there is still some lingering negative performance impact, exactly like I’ve been saying.

Apparently in the NBA this year, the rate of missing games due to respiratory illness is eight times higher than the previous 13 seasons.

Of course there are many mysteries still. Quoting a sports doctor who is turning into a Covid19-in-athletes specialist.

A lot of these people have COVID come in, and we test them. And they test pretty normal. And that’s scary because you’re telling me as the patient that you don’t feel right, you’re not playing up to par, you’re tired all the time. I’m testing you and your heart and lungs can be working just fine. Your oxygen delivery systems can be working just fine.

UPDATE 2021-09-25

Watching some interviews with the very competent seeming Dr. Bruce Patterson of Covid Long Haulers and in this video he talks about some very interesting discoveries about Covid and exercise specifically.

If you look in the exercise literature the cell type in which we found Covid protein is mobilized by exercise. So we tell all of our long haulers that the reason they have exercise intolerance or become bedridden for a day or two or a week after they give it a go so-to-speak in terms of exercise, is because these cells mobilize on exercise and then of course you’re spreading them around the body and the inflammation can resume.

I believe the cell type he’s referring to are monocytes.