Review - Cassell's Latin-English Dictionary

:date: 2024-03-28 18:33

I like hobbies that are unusual and challenging, generally to the point where normal people can no longer really comprehend the experience as sane. When it comes to reading I've been known to tackle challenging books. Despite reading most every day, this winter I managed to get through only half of one book. That book was Cassell's 1959 Latin-English Dictionary.

I can't say cover to cover because I stopped at the English-Latin section. The entire book has 928 pages and early on I thought it would be a reasonable challenge to read half that. Only as the P's dragged on past the halfway mark did I realize that for some reason, the Latin-English pages outnumbered the English-Latin by two to one (628/300). This was physically a hard book to read too. My eyesight is no longer as good as human eyesight can possibly be but for my age it's still not bad and I usually do not wear glasses when reading. With this book however, the font size was microscopic and the alien nature of the content and Latin example citations made reading glasses essential. The (ironically named) italic font, greek letters, and microscopic symbols throughout were a challenge too.

So why would somebody want to do this possibly unpleasant sounding thing? I will start by saying that I did enjoy it. I am glad I did it and consider the experience worthwhile. The first thing to consider is that by reading the entire thing I was treating this dictionary more like a book than a reference. If I need to look up a word in a foreign language computers do a fine job. Consider any book you've ever read — if it was more than a few weeks ago, the amount of specific detail you remember is next to nothing. Does that make the value of reading books next to nothing? No. Reading books is a way to really immerse yourself in a topic or story. It allows the neural networks of your mind to become stronger when thinking about the topics or themes. Recalling what some minor character did in a novel you read five years ago is not important. Mostly what you retain about such reading is that, yes, you have read that book and you either liked it or not. Occasionally there are some specific insights so important that you hang onto them too. (For example, it is bad to wake up as a cockroach! Etc.) Suffice it to say, I did not memorize any of this dictionary and I am still a poor replacement for its ordinary purpose.

But, wow, I sure did get a sense of the Latin language! Quickly reading through a simple (phonetic pronunciation) dictionary is one of my recommended techniques to learning the scope and nature of a foreign language. This one was not simple but it definitely served the same purpose of really immersing a learner in the full scope of the language.

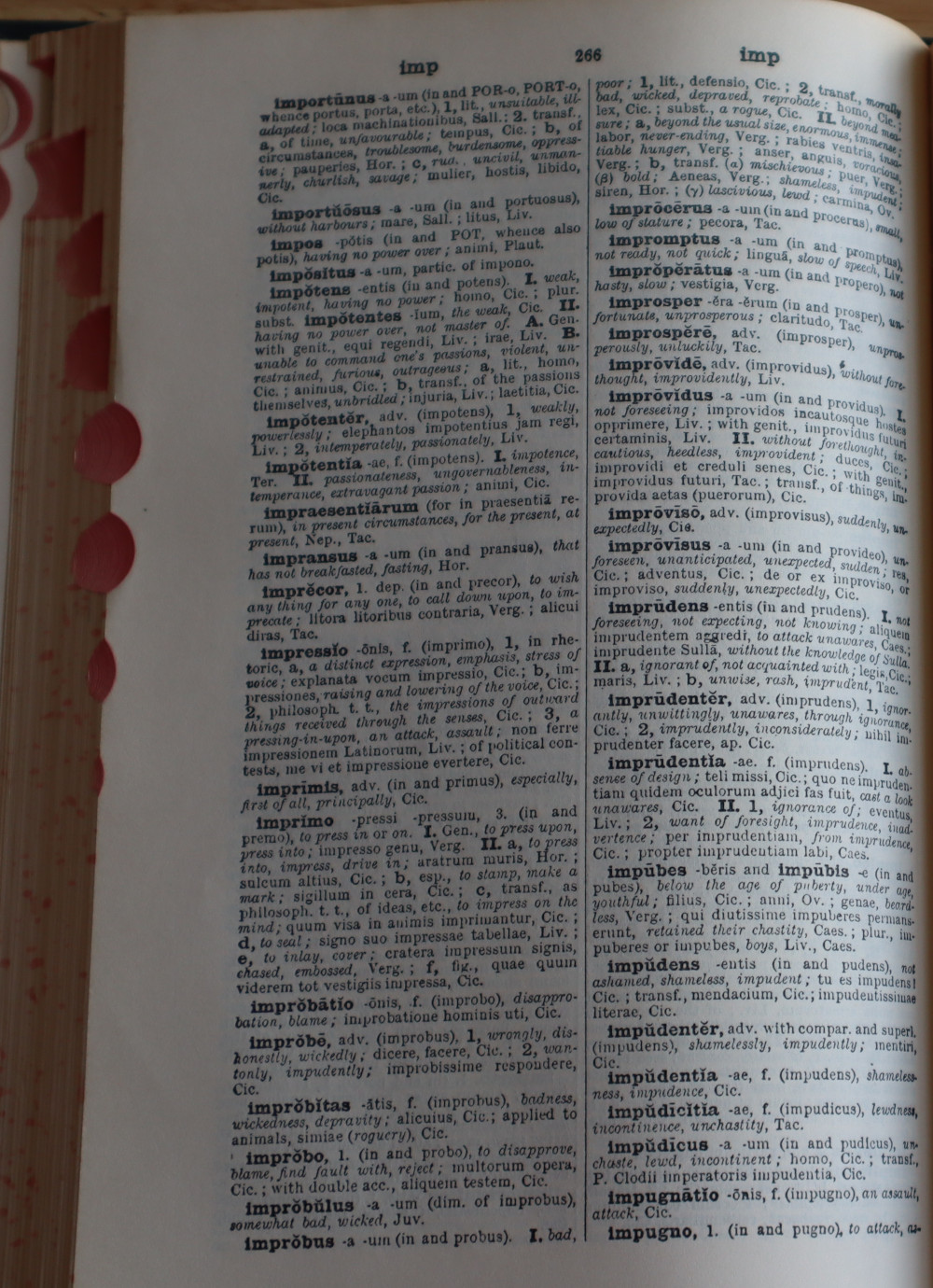

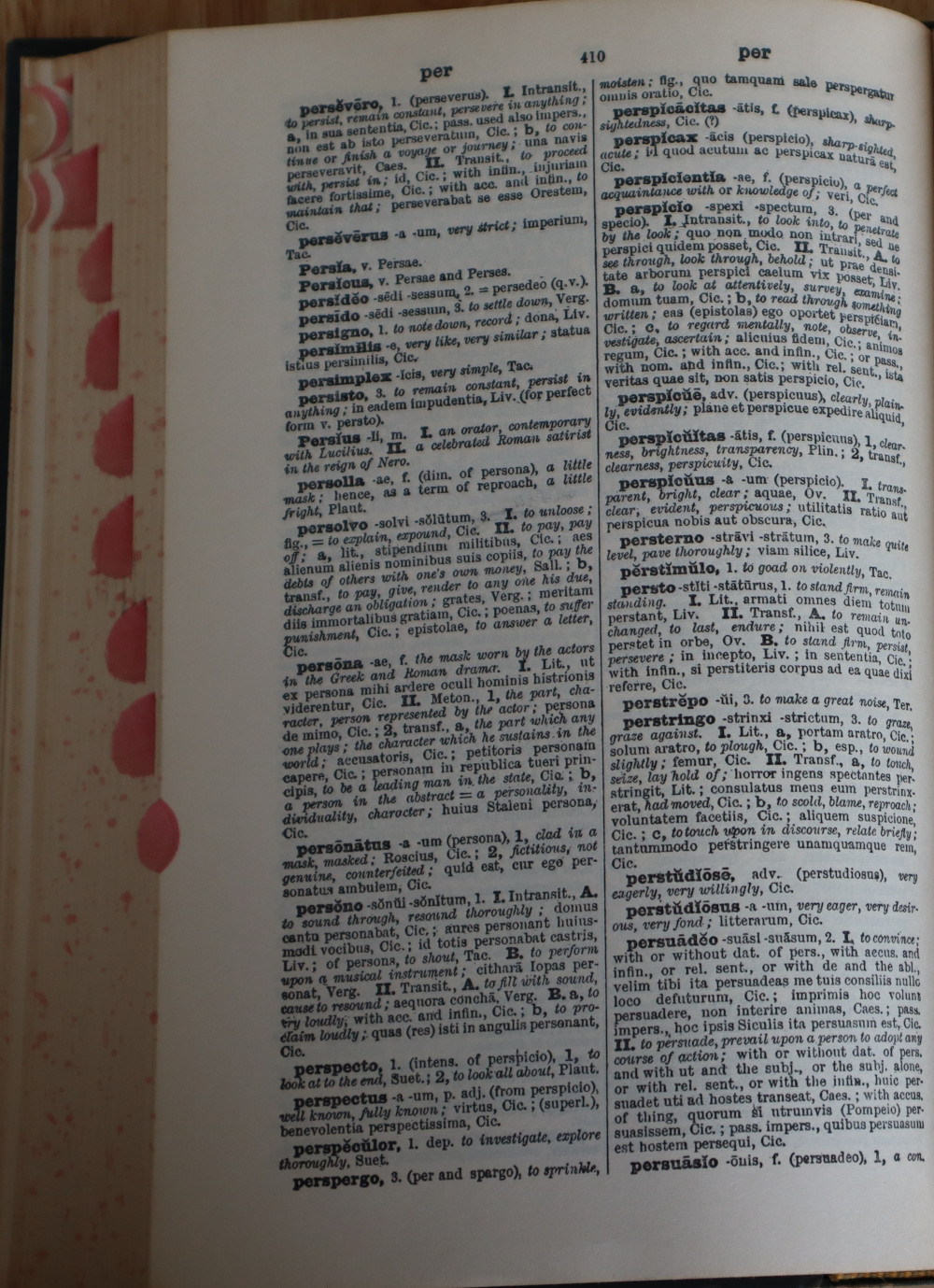

One interesting example of how reading a Latin dictionary can be helpful in understanding the scope of the language is prefixes. Latin is a heavily inflected language. This means that a core vocabulary is tweaked in small ways to convey complex meaning. For example, Latin (and any modern Romance language) is famous for its inscrutable verb conjugations. But reading all the words in alphabetic order highlights the rich character of the beginning of words too. I didn't explicitly count, but it seemed to me that most words were in prefix blocks which will mostly be familiar to English speakers. Prefixes like "com-", "con-", "de-", "di-", "ex-", "im-", "in-", "ob-", "par-", "per-", "prae-", "pro-", "re-", "sub-", and "trans-" should look familiar and important to most people speaking any European language. Reading a dictionary really helps you very deeply understand what those prefixes are all about and how they got that way. After seeing dozens of examples of how a prefix is used, you start to feel like you could, uh, re-in-vent some new words using them correctly. We do that and so did Latin speakers.

Ok, so reading a Latin dictionary is possibly helpful in learning about Latin. Great. The bigger question remains, why would you want to do that? If it's not clear by now, my real goal is not reading ancient texts but rather better understanding my own native language. English is packed with Latin! I like to read Merriam-Webster's daily Word-Of-The-Day and one day it explicitly stated the following facts.

Many of the words we use in English can be traced to one of two

sources: about one-quarter of our vocabulary can be traced back to

English's Germanic origins, and another two-thirds comes from Latinate

sources (most such words come by way of French or from Latin directly,

but Spanish and Italian have made their contributions as well).The M-W Word-Of-The-Day is actually a very interesting resource. Let's look back on the week's previous words: flout, kismet, megillah, auxiliary, genuflect, pedantic, dragoon.

I do not think that the second and third have anything to do with Latin (Turkish/Arabic, Yiddish/Hebrew). The last four clearly do — my dictionary contains "auxiliator" (helper), "genu" (knee) + "flecto" (flex), "draco" (dragon). This seems unusual to me; I feel that most weeks have an even higher percentage of Latin (see what you think).

The word "pedantic" is an interesting example too. It is not found in this Latin dictionary per se, but it highlights another fascinating aspect of our own language. What does have an entry is paedagogus. This is a bona fide Latin word, just like "pedantic" is an English one. But it is really Greek — "παιδαγωγός". The Romans, who often employed/enslaved Greeks as tutors, borrowed the word pretty much intact. Cassell's entry defines it as "a slave who accompanied children to and from school and had charge of them at home". That tumbled around through Europe until it got to English in several forms including "pedantic".

That does highlight another deep insight reading this particular dictionary offered: Greek! The Romans liked Greek in the same way Germans like English. They used it all the time! After reading this dictionary, I feel like I can now read Greek words in the Greek alphabet pretty well (my engineering degree — another arduous educational experience — didn't hurt either). I certainly got an appreciation for how much Greek is in Latin and now in English.

There is a reason that despite the fact that my grandmother quit school to work in Leicester's sock factory at the age of 14, she was actually taught a decent amount of both Latin and Greek. It wasn't to decode ancient texts but rather to be more exact and expressive with her own native language. Reading a dictionary's worth of Latin affirms this. Every page was like a month of reading M-W's Word-Of-The-Day. Every page contained at least one entry where I was amazed by some bit of linguistic trivia. Often it was a deeper understanding of the intricacies of Latin itself which I thought I knew (e.g. "nemo" is nobody, but really is a contraction of "non homo" or "no man"). But mostly I was fascinated at the connection to modern English. For example, the word "schola" (originally from Greek "σχολη") is interestingly defined as "leisure, rest from work; hence learned leisure, learned conversation, debate, dispute, lecture, dissertation." Basically it's a place where people idly hang out and talk about doing nerdy things like reading a translation dictionary of an ancient language. We have blogs for that kind of thing now!

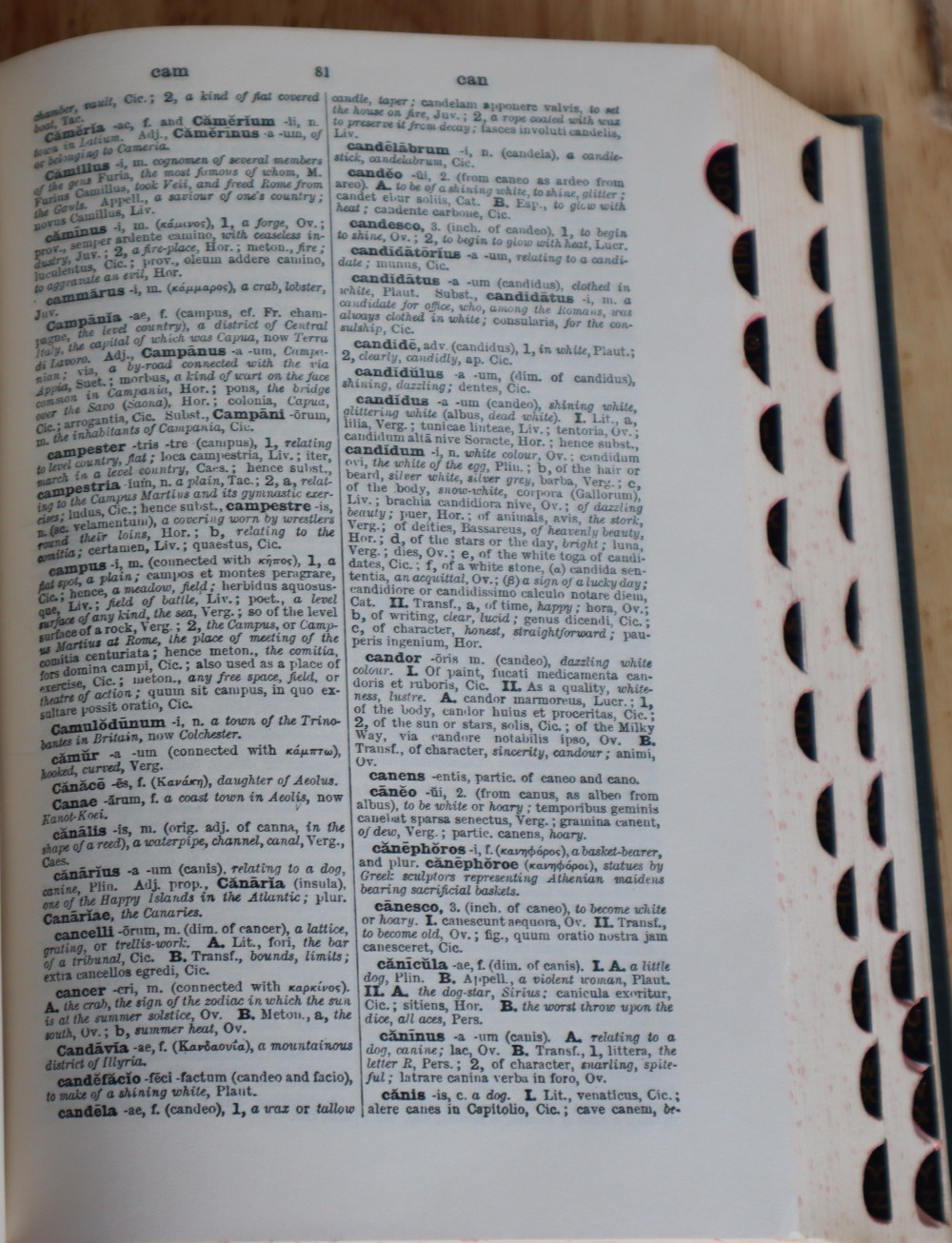

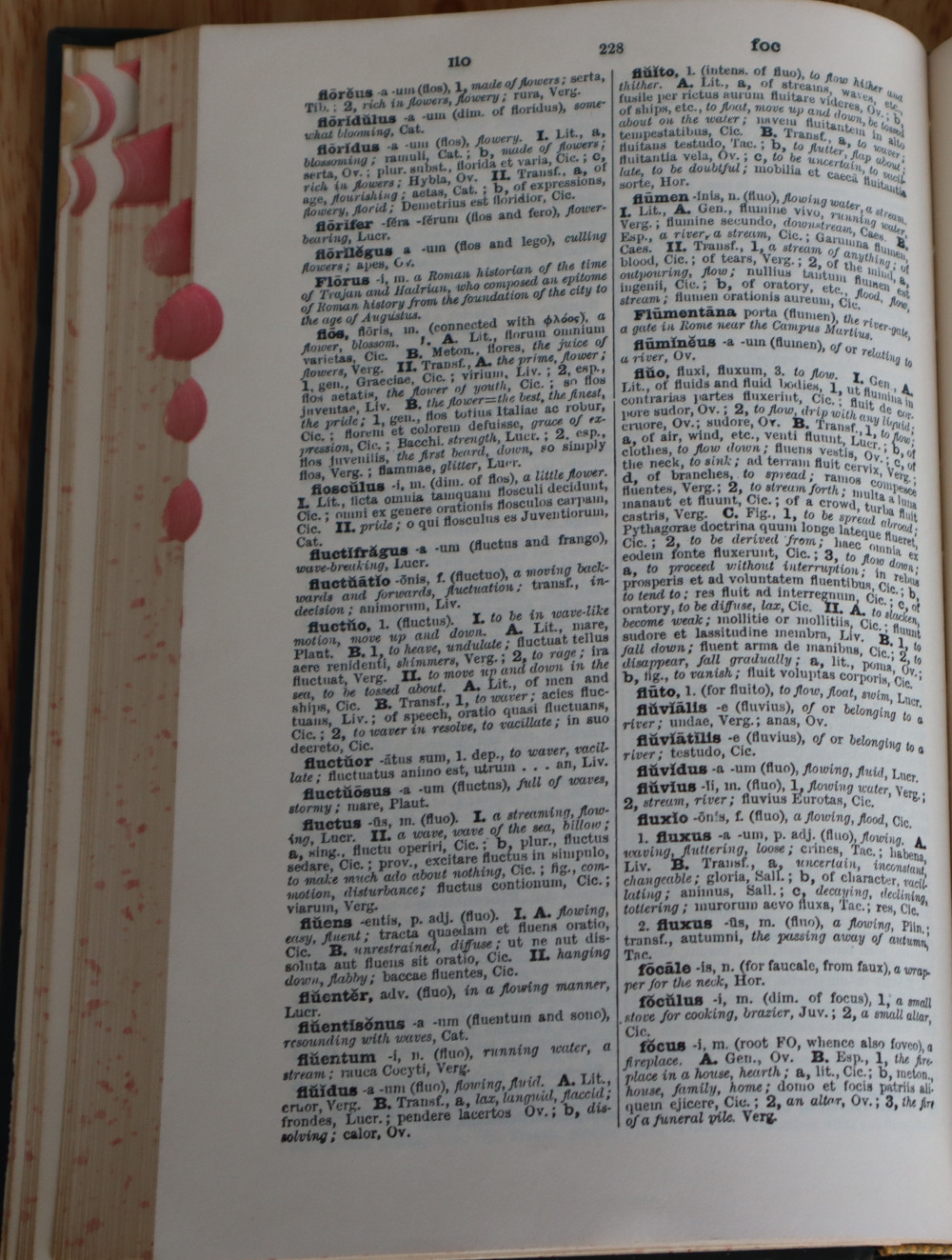

Take a look at these sample pages and see for yourself how much is quite familiar to English speakers.