I am well known to be someone who is interested in the future of transportation but my heretical belief is that infrastructure designed for the transportation of the past may not be appropriate for the future. Shocking, right? Well, to understand that exact topic better, I just finished M.G.Lay’s Ways Of The World: A History Of The World’s Roads And Of The Vehicles That Used Them. This book was organized about as well as a collection of several thousand diverse bits of historical trivia can be. There was some interesting etymology. The history lessons were quite interesting to me. Even relatively recent history — in the lifetimes of people I have personally known — has been completely forgotten. For example, 2000km of electric trams in Los Angeles? Yup. Many of LA County’s neighborhoods (e.g. Beverly Hills) were built by rail companies expanding. Actually, I’m sure it was more like 1200 miles at the time but the author really loves metric units and while that was sometimes strange, as a metric enthusiast myself, I give it a thumbs up.

It’s hard to know where to start with this book. Such a profusion of interesting facts! ("Interesting", assuming you care at all about transportation.) All I can do to give a sense of it is record some of the tidbits I found especially interesting.

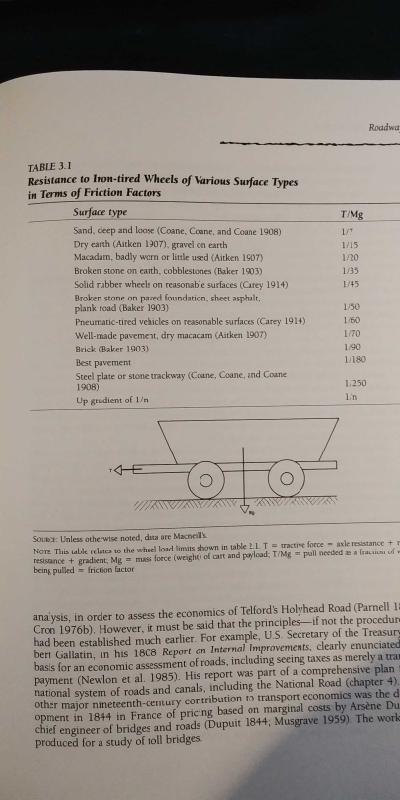

Here’s a table which I found very interesting and useful for professional reasons but just glancing at the cropped text below gives a sense of the explosion of facts in this book. Every page is like this!

It’s amazing how slow the first speed limits were. (p194) Let’s just say that I would probably have had a lot of speeding tickets if I could take my bicycle back in time. And yes, I’m considering the conditions of those roads.

The railways were at first major sponsors of roads because it allowed people to get to the stations. I guess this is sort of like Xerox (PARC) originally sponsoring office computing and then finding it eradicating much of their core business.

p139 The Baltimore Ohio Railroad seems to originally have been envisoned as a competitor to the Erie Canal. And even more interesting it was envisioned as being horse powered. During its construction, steam was able to demonstrate superiority. The Erie Canal’s days were numbered.

In 1904 cars replaced horses for transporting US presidents. I find that benchmark very interesting. When will the first US president typically ride in an autonomous vehicle?

The British Red Flag Act (of 1865) is interesting. According to Wikipedia it created "a policy requiring self-propelled vehicles to be led by a pedestrian waving a red flag or carrying a lantern to warn bystanders of the vehicle’s approach." I am not even kidding. This actually boosted Britain’s cycling culture for a while.

Roads have always been military artifacts. Outside of the very famous DARPA challenges I can’t believe the military isn’t more conspicuous with its autonomous vehicle agenda (if it even still has one).

It would be interesting to consider freight mode cost effectiveness factoring in maintenance costs of the required paths.

p98 In the mid 1930s, "Idealistically, autobahn construction was seen as a trial mobilization and as embodying Nazi ideals of national character, sprit, strength, and beauty." On p315 we learn that "The autobahn’s chief advocate was Fritz Todt…"; I found that ironic since the word "todt" in German means "dead".

p102 "Following emancipation, Georgia passed legislation allowing convicts to be used for roadwork, a move that ‘revolutionized highway construction in Georgia’. The use of convicts for roadmaking became fairly widespread throughout the United States."

p124 "In 1664 France introduced a further stage system using lighter two-wheeled carts known as chaisses, or shays. In a system known as post travel, travelers supplied their own chaisses and hired horses from the post houses." Doesn’t that sound just like a futuristic electric vehicle battery swap?

p135 I had not realize how profound streetcars were for intensifying the size of cities. In the late 19th century many cities doubled within a decade when this technology arrived.

p144 "The bicycle was defined as the ‘poor man’s carriage’ and initiated humanity to that new twentieth-century right, the freedom of all citizens to travel when and where they please."

p175 The first road "accidents" involving cars were in 1896 — London and New York each got one. The US one involved a car hitting a cyclist.

p199 The decision to drive on the right or left side of the road turns out to be so complex I can’t even begin to summarize it. That stuff you’ve heard about where it’s easy for knights to high five each other or whatever turns out to be only a small part of the picture. Really, it’s way more complicated than I imagined.

p217 Talking about tar, "Like bitumen, it had some popular uses outside roadmaking. For example, in the eighteenth century tar water rivaled soda water in popularity and the presence of tar was thought to improve the taste of wine."

p224 "Because many roads built for royalty used setts rather than rough cobbles, they came to be known as pave' du roi." This shows that not only is infrastructure change possible, it can actually be brought about by rich toffs. You hear that Sergey Brin?

p225 This was a pretty funny reason that contributed to the development of modern paving systems. "Discontented Irishmen had similarly used setts for missiles in 1864 [rioting]. For such reasons, there was a strong official preference for a more coherent and less throwable pavement surfacing."

p233 An interesting tidbit — a researcher in 1897 claimed that Buffalo, NY had more asphalt paving than any city in the world (followed by Berlin). I very much believe that Buffalo, with it’s Niagara power generation and industry, was the Silicon Valley of exactly a century ago.

p239 "Trucks also made it possible to bring good roadmaking materials over much larger distances than had been feasible with horse and cart, a major benefit. For all these reasons the length of the more expensive asphalt rural roads went from zero in 1914 to 16,000km in 1924." This is an example of how the technology that required the major and expensive infrastructure change also provided means for making that exact upgrade. There is a very important lesson here for autonomous vehicles that companies like Waymo refuse to see.

p283 "Some 502 iron bridges — or a peak of 25 percent of all metal bridges — failed in the United States between 1870 and 1890…" Wow. It’s hard to appreciate how new the bridge technology we take for granted now is. In my lifetime when the Coronado Bridge was opened, the kind of technology for making such massive high spans with welded steel could not have been older than, say, FORTRAN is now.

p295 "[A bridge live loading study] had its precedent in earlier live loading studies, which used three hundred workmen to test panels for London’s Crystal Palace in 1851. Stoney’s experiment involved packing Irish laborers onto a weighbridge." Being used as engineering crash test dummies — no wonder those Irish were fond of rioting!

p307 Wikipedia indicates that one of my favorite philosophers, Bertrand Russell, was the first to note something called the Marchetii constant where people always seem to commute/travel about 1 hour per day and have done so since neolithic times regardless of the means of transportation available to them. This book strongly supported this idea. What is important to also acknowledge is that although we (generally) now still do the same hour that tram riders did 100 years ago, what has changed is that a commute in a car is actual hard work — that is why people get paid to drive trucks etc.! Gone are the better days where you could take a nap or read the newspaper. Since the added convenience seems to be mostly taken up with town expansion I can’t see how the car is any kind of enviable progress over electric trams.

p309 The first motel was in San Luis Obispo. It’s funny to think of southern California as having the oldest of anything but there you go. I’ve even stayed in a motel there and it was pretty nice as far as such things go.

p312 "In many cases the major change effected by road construction was an increase in the number of people traveling by road, rather than improvement in the level of service offered to existing road travelers." In other words, if you love traffic and pollution, build more roads. Works every time. This echoes the excellent book Traffic.

Summary

-

The history of roads is important, complicated, and almost entirely unknown by nearly everyone who uses them.

-

If you really like roads, you’ll like this book. If you’re a professional road expert, this book will ensure that you possess an inexhaustible supply of road trivia to impress your colleagues with.

-

I will assert that autonomous vehicles will not happen without some kind of infrastructure change. If I am wrong about this, it will be a break with history so profound that the autonomous vehicles per se will not be the interesting development.

-

Autonomous technologists blithely make the mistake to have a normal person’s interest in road craft — i.e. none at all. (I’ll give partial credit to Elon Musk who does have some laudable infrastructure projects like The Boring Company. I even encourage ideas like Hyperloop that are probably at odds with the laws of physics but at least innovative and thought provoking.)

-

At this point in history, road makers are intensely struggling with the difficult problem of how to completely ignore the obvious and enormous potential of autonomous vehicle technology. The moment infrastructure planners admit that today’s cars are already anachronistic is the moment real progress can begin.

-

If you’re in the autonomous car business, I think it’s important to get a bit of the perspective about roads this book can give. To not be properly aware of the road is no worse for an autonomous car as for its designer.